I was incredibly honoured to once again facilitate this annual lecture in memory of Dr. Barbara Tatham at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University.

Barbara was a medical student at McMaster University and went on to become an innovative Family and Emergency Room Physician and collaborative Medical Educator. After enduring a courageous battle with cancer, at the age of 32, Barbara died on October 16, 2019, a few short weeks after delivering her final extraordinary undergraduate medical education lecture, Barbara left us with her last lecture, a precious legacy, recorded at McMaster, selflessly demonstrating her indomitable spirit and compassion.

We have been fortunate to maintain contact with Barbara’s family since 2019. Their hope is that medical students while remembering Barbara’s empathy, will consider their own humanity as they go on to care for patients, families and themselves.

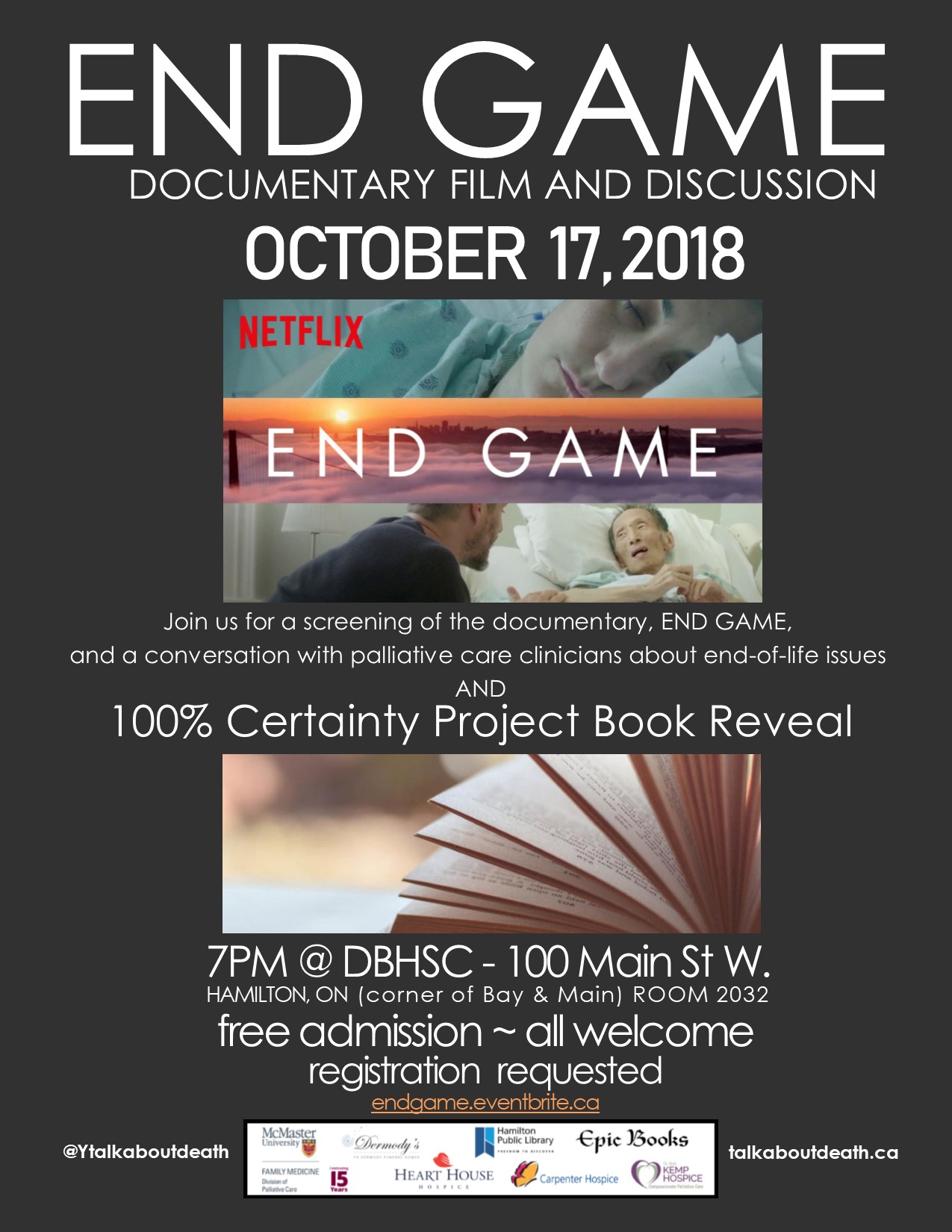

End Game Documentary and Discussion

Excited to co-host and participate on the panel for the launch of the 2018-9 season of "The 100% Certainty Project. Death: Something to Talk About". Join us for a screening of the Netflix documentary, "END GAME" followed by a conversation with Palliative Care clinicians.

Our free public event at McMaster University features the brilliant documentary "End Game" from Shoshana Ungerleider, MD highlighting the essential tenets of Hospice Palliative Care. The film showcases the collaboration, compassion and communication as the heart of person and family-centred care at UCSF Medical Center with Steven Pantilat and the extraordinary interprofessional team. The film also highlights the brilliant work of Zen Hospice Project, showcasing Dr. BJ Miller and the extraordinary interprofessional team in Hospice.

Please join us for this engaging event! While the event is free, registration is required via Eventbrite via https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/end-game-documentary-and-discussion-tickets-50535681584

The Conversation Placebo

"What’s often overlooked is that the simple conversation between doctor and patient can be as potent an analgesic as many treatments we prescribe."

When Patients Leave ‘Against Medical Advice’

"As physicians, we must explore our patients’ reasons for wanting to be discharged and have open and truthful conversations with them. We assume that keeping them in the hospital is always better for their health. But health encompasses the physical, mental and psychological.

In the end, my patient’s leaving was not about our therapeutic alliance. It was not about me at all. It was about her, the patient, as it should be."

Storytelling in Grief: Honouring Connections while Celebrating Legacies #hpm

“I don’t know how to tell my family about the diagnosis…” “I haven’t told my kids that I’m dying…”

Families often reeling following the diagnosis of Cancer or other life-limiting diseases, struggle with how, and when, to have those essential conversations. I am a Social Worker and for the past 17 years have had the privilege of caring for people facing a life-limiting illness. It is an intimate and profound experience - sitting alongside people as they face end-of-life. They share their hopes and fears - about living and dying - and about caring for and leaving behind those they love. Trying to protect their families but also wanting to prepare them. Whether they speak lovingly about a partner, or children, or siblings, parents or best friends… grieving these losses begins at time of diagnosis.

While treating and managing the disease is important - equally important is caring for the person diagnosed with the disease. What is truly important to them? Who is important to them? How do we provide support in a manner that is congruent with their values and wishes? How do we normalize grief following a diagnosis, and in turn, sit alongside them creating safe spaces - and time - to share their grief should they so choose? As clinicians, we can facilitate supportive interventions at any stage of illness and ideally engage the entire family. Sadly, many families - and specifically many children and youth remain uninformed following the diagnosis of a life-limiting illness, largely resulting from parents need to “protect” and their fear of not knowing what to say. This phenomenon is not rare as it also extends to healthcare professionals, with many reporting fear and uncertainty as to how to best support grieving families and children. This is true whether a child has been diagnosed with a life-limiting illness, or the parent of a child has been diagnosed. Understandably, if the psychosocial needs of families, specifically children and youth remains unaddressed, it only serves to create additional distress for parents and caregivers.

As a Palliative Social Worker I recognize the importance of creating safe spaces and time to have these conversations - to support families in telling their stories, celebrating their connections, and should they so choose, to openly and collectively share their grief. A specific legacy project created opportunities for families to do just that - to hold on, while letting go. I have completed this project with many families facing a life-limiting disease - following diagnosis, throughout the illness, at end-of-life and following the death of a loved one. This can be completed with children of all ages and regardless of the make up of the family - large or small, we meet together and explore their understanding of the diagnosis, the impact of the illness while also celebrating and honouring connections. That Project? While the results have been profound, the activity is, quite simply, creating a “Hug”.

To be clear, this is not a professional boundary violation, but in fact, a creative legacy project that can be done by anyone, anywhere, at any time. In obtaining consent from parents and caregivers, I explain that this is an opportunity for the family to collectively talk about the illness, share stories and experiences, communicate concerns, dispel fears, foster support and enact plans. I introduce this activity as a symbol of their unending love – and the Hug can be taken anywhere - to chemo daycare, during an admission to hospital or hospice, or even once someone has died – this “hug” is also something that can be buried or cremated and remain with a loved one forever…

I assure you this experience is more than a creative activity - it is an intimate and collaborative experience for the family to create a lasting memory. While each experience is unique and the degree to which some “patients” may be able participate varies, in each situation, the family gently accommodates their loved one. What remains universal are the shared laughs, tears and a multitude of stories - reminders of shared experiences and memories of their lives together.

But perhaps I should explain… I feel it is important to outline the essential elements required for this intervention… Specifically, informed consent from the family, clean bed sheets, colourful markers, scissors and glitter. It is simply a matter of laying a sheet on the ground, then a family member lays down on the sheet while another family member traces their outstretched arms and outstretched fingers. After sitting up, lines are drawn to connect the tracings of each arm and then cut along the lines. Although tantamount to making a scarf – it is, more importantly the outstretched arms of their loved one, it is a personalized “Hug”. The child, or partner, sibling, parent or friend then adorns their hug with messages and images and reminders of the shared connection with their loved one - in essence, the “Hug” becomes a tangible expression of their love.

While I involved partners, children, siblings, cousins and friends in this activity long ago I wondered, what if their loved one (or the “patient”, to be clear) also wanted to reciprocate? I began asking patients about this and the suggestion of leaving this touching legacy was always met with resounding approval. While this always requires patient consent and discussion throughout, I have completed this activity with people who were ambulatory as well as people who were bed-bound. While collectively engaging the individual and family, for those who are bed-bound, we carefully slide a folded sheet behind the back of their loved-one. Throughout the activity, the family shares stories and memories, while tenderly helping to hold and trace the outstretched arms and fingers on each hand - every action and movement becomes an incredibly intimate experience. In the case of pathological fracture, we have used the singular tracing of one arm to make a mirror image - completing the hug. Taking that singular hug and laying sheets over top, additional copies are then traced for each family member. This not only engages entire families at the bedside, but also creates a lasting legacy for the surviving family. We often discuss sewing material from favourite blankets, shirts or sweaters on the reverse to preserve a tangible and personal connection.

I have completed this activity when families speak a language different from my own. Despite only being able to communicate through an Interpreter, the conversation remains seamless throughout as we create a beautiful and moving tribute for their family while they collectively support each other in their shared love and grief. While many young couples anticipate milestones like a wedding or the birth of a child, I have also facilitated this project at the bedside of the dying parent together with their young adult children, creating a space to share their hopes and stories while honouring their legacy. This supportive intervention has also bridged great distances, when families were thousands of miles apart. After completing the activity with the patient and family at the bedside, I encourage them to share the idea with extended family and friends across the country and in one specific case, family members of all ages from across the country made Hugs and sent them by courier to the bedside of their dying loved one. Their many colourful “Hugs” surrounded her when she died, each and every one told a story and was on display around her room as a meaningful and tangible connection. Much to the comfort of the family, each and every “Hug” was later buried with her. I have also completed this project with children following the death of a parent, it is especially important for those who were not informed about the illness or were unaware that death was expected. It is so essential to create a space for children to grieve alongside their families to share their thoughts, shed tears, and express the range of their feelings, including grief. We talk about what it feels like to receive hug from someone you love and the opportunity to create a lasting memento to leave with their parent as an expression of their unending connection. Although a parent - or any loved one might die before families and friends have an opportunity to say goodbye, we can still create opportunities for families to collectively share their love and express their sorrow while honouring the legacy of their loved one.

I believe as Health Care Professionals, we have an obligation to provide empathic person and family-centred care. From time of diagnosis we have an opportunity to facilitate honest communication, and in turn, promote adaptive coping strategies for those facing a life-limiting illness. In doing so, we can provide invaluable opportunities for families to connect, and collectively process experiences from time of diagnosis through to end-of-life, and into bereavement. I feel extraordinarily privileged that families allow me into their lives - to share their stories, their love and their grief. However brief our time may be together, I hold that time as sacred and do all I can to create a safe-space to foster these connections while honouring the legacy of those living and dying.

Rappelling Together, Downward and Inward #Compassion @ParkerJPalmer @onbeing

“When I came home and went back to work, I looked around and said to myself, ‘If only we could see the 'inward rappel' so many of us are making right now — the daunting challenges so many folks wake up to each morning — we’d have more compassion and offer each other more support. If our inner struggles were more visible, more compassion would flow.’

I know there are situations where it's dangerous to be transparent about your fears — though I also know there are ways to create safe space to get the support we all need. But whatever our situation, all of us can exercise an empathetic imagination about the ‘inward rappels’ others are making, just as the poet Miller Williams urges us to do:

Compassion

Have compassion for everyone you meet

even if they don't want it. What seems like conceit,

bad manners, or cynicism is always a sign

of things no ears have heard, no eyes have seen.

You do not know what wars are going on

down there where the spirit meets the bone.”

.The Gift of Presence, the Perils of Advice @PARKERJPALMER

“Here’s the deal. The human soul doesn’t want to be advised or fixed or saved. It simply wants to be witnessed — to be seen, heard and companioned exactly as it is. When we make that kind of deep bow to the soul of a suffering person, our respect reinforces the soul’s healing resources, the only resources that can help the sufferer make it through.

Aye, there’s the rub. Many of us ‘helper’ types are as much or more concerned with being seen as good helpers as we are with serving the soul-deep needs of the person who needs help. Witnessing and companioning take time and patience, which we often lack — especially when we’re in the presence of suffering so painful we can barely stand to be there, as if we were in danger of catching a contagious disease. We want to apply our ‘fix,’ then cut and run, figuring we’ve done the best we can to ‘save’ the other person.”

@BreneBrown The Power of #Vulnerability: #Courage, #Compassion and #Connection

"Feel the story of who you are with your whole heart...

Courage to be imperfect...

Compassion to be kind to themselves first and then to others. We can't practice compassion with others if we can't treat ourselves kindly...

Connection - this was the hard part - as a result of authenticity they were willing to let go of who they thought they should be in order to be who they were... fully embraced vulnerability they believed that what made them vulnerable made them beautiful...

to do something where there are no guarantees..."

@BreneBrown on #Empathy. "What makes something better is connection"

"What is the best way to ease someone's pain and suffering? In this beautifully animated RSA Short, Dr Brené Brown reminds us that we can only create a genuine empathic connection if we are brave enough to really get in touch with our own fragilities".

Letting #Patients Tell Their #Stories. @DhruvKhullar

“As we acquire new and more technical skills, we begin to devalue what we had before we started: understanding, empathy, imagination. We see patients dressed in hospital gowns and non-skid socks — not jeans and baseball caps — and train our eyes to see asymmetries, rashes and blood vessels, while un-training them to see insecurities, joys and frustrations. As big data, consensus statements and treatment algorithms pervade medicine, small gestures of kindness and spontaneity — the caregiving equivalents of holding open doors and pulling out chairs — fall by the wayside.

But all care is ultimately delivered at the level of an individual. And while we might learn more about a particular patient’s preferences or tolerance for risk while explaining the pros and cons of a specific procedure or test, a more robust, more holistic understanding requires a deeper appreciation of ‘Who is this person I’m speaking with?’

In Britain, a small but growing body of research has found that allowing patients to tell their life stories has benefits for both patients and caregivers. Research — focused mostly on older patients and other residents of long-term care facilities — suggests that providing a biographical account of one’s past can help patients gain insight into their current needs and priorities, and allow doctors to develop closer relationships with patients by more clearly seeing ‘the person behind the patient’.”

When Cancer Treatment Offers Hope More Than Cure

"I turned back to my patient, still holding her hand. 'How about we take a little break from the treatment?'

She nodded, and we sat in silence again. After a while, she asked 'When we gonna get started on chemo again?'

I looked uncertainly at her and then at Mr. Boo. He looked back at me, awaiting my reply. This time, I rearranged myself to sit up a little straighter in my chair.

'Well, I have to wonder if giving you more chemotherapy is the right thing to do, with all that you’ve been through. I’m wondering if we should be talking about bringing more care into your home, to assist both you and Mr. Boo. Maybe even hospice.'

I had said the word."

Death, the Prosperity Gospel and Me

"It is the reason a neighbor knocked on our door to tell my husband that everything happens for a reason.

'I’d love to hear it,' my husband said.

'Pardon?' she said, startled.

'I’d love to hear the reason my wife is dying,' he said, in that sweet and sour way he has.

My neighbor wasn’t trying to sell him a spiritual guarantee. But there was a reason she wanted to fill that silence around why some people die young and others grow old and fussy about their lawns. She wanted some kind of order behind this chaos. Because the opposite of #blessed is leaving a husband and a toddler behind, and people can’t quite let themselves say it: 'Wow. That’s awful.' There has to be a reason, because without one we are left as helpless and possibly as unlucky as everyone else".

They Brought Cookies: For A New Widow, Empathy Eases Death's Pain

"So I'll tell you the positive effect and you know it already: empathy is pain's best antidote. It is, says Robert Burton in his astonishing Anatomy of Melancholy, 'as fire in Winter, shade in Summer, as sleep on the grass to them that are weary, meat and drink to him that is hungry or athirst.'

The pain doesn't go away; but somehow or other, empathy gives the pain meaning, and pain-with-meaning is bearable. I don't actually know how to say what the effect of empathy is, I can only say what it's like. Like magic".

The Gift of Bad News. #Dying #Coping #Healthcare

"We’ve all been told we should live each day as if it were our last, but how many of us truly can? Life is a journey. We’re in the middle of it. When we hear the news, we know — for the first time really know — our journey will end. What do we want from our doctors at that moment? What do they want from us? No matter where we sit, we are infinitely far apart and impossibly close. They have given us something no one else on earth has ever given us before, and we are transformed."

When a child is dying, the hardest talk is worth having. #PedPC

"Conversations about the end of life are hard for most people. But they can be especially sensitive for parents guiding children through terminal illnesses. They often struggle to discuss death because they don’t want to abandon hope; children, too, can be reluctant to broach the subject.

But pediatric specialists say the failure to discuss death — with children who are old enough to understand the concept and who wish to have the conversation — can make it harder for all involved.

A conversation could help children who are brooding silently suffer less as they approach death. It would also ensure parents know more about children’s final wishes".

The Difference Between Empathy and Compassion Is Everything.

"Empathy is a gateway to compassion. It’s understanding how someone feels, and trying to imagine how that might feel for you — it’s a mode of relating. Compassion takes it further. It’s feeling what that person is feeling, holding it, accepting it, and taking some kind of action".